RETURN TO HOME PAGE

FEEDBACK

|

July-August 2010 RETURN TO HOME PAGE FEEDBACK |

By Corrie M. Anders

"Nearly every image, whether of places or people, whether early or late, wears his trademark of gentle, whimsical irony."

--Wallace Stegner, in the foreword to Leo Holub: Photographer (1982)Noe Valley photographer Leo Holub included many celebrities in his circle of friends. Photographer Imogen Cunningham was a regular guest at Holub's home on 21st Street. Novelist Wallace Stegner, photographer Ansel Adams, artist Ruth Asawa, and painter Richard Diebenkorn were longtime comrades.

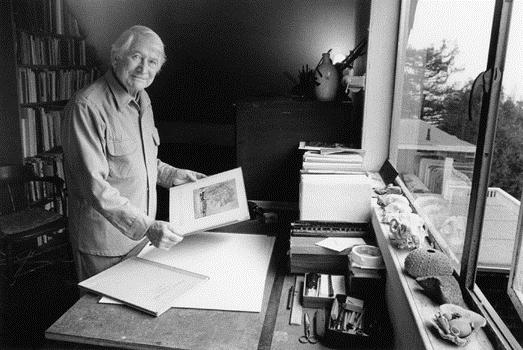

During his later years, photographer Leo Holub archived and catalogued his prints for donation to the Smithsonian Institution. But more than that, he devoted his time and energy to family, neighbors, and friends. 2004 photo by Pamela Gerard Like his famous friends, Holub produced hundreds of works of art, including several that are now a part of collections at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the de Young Museum.

But during his career in photography and as the bedrock of Stanford University's photography program, Holub rarely sought the limelight. He was quiet and unassuming--so inconspicuous that the subjects of his photographs sometimes forgot his presence until the click of the shutter.

In the long run, that didn't matter.

His gentle demeanor, his playful wit and charm, his devotion to his family, and his willingness to share his talents with others--all those things made the bright shining light that was Leo Holub.

The distinguished photographer, loving husband, and 53-year Noe Valley resident died on April 28 at the age of 93.

He died of "natural causes...at home and at peace," said his son, Eric Holub. Friends and colleagues are planning a memorial gathering in the fall.

Holub was known for his simple, iconic black-and-white images. His photos documented San Francisco's changing urban landscape; contemplative moments in the lives of friends, students, and artists; and scenes in nature, such as a garden snail peering over the precipice of a high concrete wall.

Florence and Leo Holub, snapped on 24th Street in 1995. Photo by Sally Smith Not only did he capture unique impressions of the world around him, he also took delight in snapping photos for a book jacket or album cover, or for his neighborhood newspaper, the Noe Valley Voice. (Regular Voice readers already know much of Holub's personal story. His wife, Florence Holub, immortalized him in "Florence's Family Album," published from the 1980s to 2009.)

"He was very generous with his photos over the years," said Voice editor Sally Smith. "But he also was a good friend--an amazingly kind, sweet man. We'll miss him."

Holub's largesse was legendary. When 21st Street resident Stephen Vincent needed a picture for his Facebook page, he turned to his neighbor and friend of a quarter century.

"Why would I give up the opportunity to use a photo taken by Leo for one taken by someone who wasn't as gifted as Leo?" said Vincent.

It's hard to miss Holub's presence in the office of Dr. Barry Kinney on 24th Street, who has been the Holubs' family dentist for two decades.

Hanging on a wall in the entryway is a signed photograph of the San Francisco docks--shot in 1950 from the fantail of a ferry steamer as it pulled away from the wharf for a trip to Oakland--with the Ferry Building framed (see page 10).

"Leo brought it by one day, along with some others he had in his collection," Kinney said. "He said, 'Pick your favorite, and you can have it.' I said great. I went out immediately and framed it. It is such a great picture."

Wendy Tice-Wallner, who moved in next door to the artist in 1988, called him the "neighbor everyone would wish to have." When she traveled, Holub would pick up her mail (without being asked) and keep a careful eye on the house. Then there was the time her mother visited from the East Coast and Holub "went out of his way to entertain her and take her to the museum," she said.

Holub frequently invited Tice-Wallner and her partner, Megan Penrose, to stop by. He would "always open a bottle of champagne, put some nuts into a bowl, and we'd have a great visit," Tice-Wallner said. "He really loved to do that." She also noted how devoted he was to wife Florence, whose health has declined in recent years.

San Franciscobased art historian Paul Karlstrom, who called Holub "my best friend, my best buddy, and I was his," interviewed Holub in 1997 for an oral history, which is now in the Smithsonian Institution.

"His gentleness and apparent lack of ego...really come through in his images," said Karlstrom. "The images convey a very genuine sense of the man."

Holub authored two books, and his prints can be found in private homes, galleries, and museums around the country.

Still, he never received the critical praise and public adulation accorded such 20th-century artists as Adams and Cunningham. The principal reason, according to Karlstrom and other art specialists, was that "he absolutely was not inclined to self-promotion.

"Even Imogen was aware of the need to do that, and Adams was a big self-promoter," Karlstrom said. "But I think we'd all agree that Leo was missing the gene for self-promotion."

Holub was born of Czech descent in 1916 in the tiny Ozark Mountain town of Decatur, Ark., the son of a blacksmith and housewife. His family lived for several years in Oklahoma and New Mexico before moving to Oakland, Calif., when he was 7 years old. He graduated from Oakland High School in 1934.

Though he enjoyed photography--his first camera was a 14th birthday present from his mother--Holub dreamed of becoming a painter. He couldn't afford college, initially. To earn his way, Holub toiled in Sierra Nevada gold mines for a couple of years, in his father's old craft, and saved enough money to attend the Chicago Art Institute in Chicago in 1935. In his second year in Chicago, his funds ran out and Holub transferred to the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco.

There, he studied painting, life drawing, anatomy, and art history. He also met his future wife, Florence Mickelson. Mickelson and Holub shared a fashion illustration class, and their first date, fortuitous as it was, happened after several classmates scheduled a group trip to a local hospital to visit an ailing professor.

The two were the only ones who showed up.

"We stayed with [the professor] for a while. Then she had to rush home, and so I called a cab and took her home," Holub recalled in his interview with Karlstrom. "There went my dinner for three nights... and that was the start of it."

Florence and Leo tied the knot two years later. Eventually, they would raise three sons--Michael, Jan, and Eric--first on Kingston Street in the Mission District and later in their brown-shingled house on 21st Street, which they purchased in 1957 for $7,600. Holub built a dark room and workshop in the basement of the six-room house.

Holub left school around the time of his wedding to work as a product designer and then as a printer for a lithography firm. During World War II, he spent four years as a civilian ship's rigger for the Navy. Later, he worked for several commercial companies and two city agencies before landing a position in the late 1950s with the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency. That job required quite a bit of photography of old buildings, many of which were marked for demolition.

He left the urban renewal agency in 1960 to join Stanford, doing architectural photography for the school's planning office. As he moved around campus, Holub took pictures of students, dogs, bicycles, and everyday scenes that caught his eye. The campus pictures led to Holub's first solo exhibit in 1964--which set an attendance record at the school's art gallery.

In 1969, school administrators asked him to launch a photography department. Students were so eager to enroll, they camped out overnight before the first class. Over the next dozen years, Holub taught photography to more than 4,400 students before retiring from the faculty in 1980, as senior lecturer emeritus.

Along his photographic journey, Holub authored Stanford Seen (1964), a collection of 235 photos featuring students on the Stanford campus, and Leo Holub, Photographer (1982), an award-winning compilation of 125 of his best pictures taken during a 40-year span.

Retirement was hardly the denouement of his career. Menlo Park art collectors Harry and Mary Margaret Anderson, who years earlier had seen a Holub portrait of Diebenkorn, commissioned Holub to photograph 100 prominent 20th-century artists at work in their studios. When the cross-country odyssey was completed a decade later, Holub had focused his lens on everyone from pop artist Roy Lichtenstein and sculptor Richard Serra to Noe Valley painter Paul Wonner and Glen Park artist Bruce Conner.

In his 90s, Holub continued to spend many hours in his basement darkroom--cataloguing his negatives and prints for the Smithsonian. His research papers have been donated to Stanford University.

In 2006, Stanford held a retrospective of his work. The following year, the David Himmelberger Gallery in San Francisco exhibited Holub's photos at its own show. During a second tribute at the gallery in 2009, Holub told an opening reception that he was tiring and that the exhibition would be his final one.

"Maybe somehow he could sense he was coming to the end of his life," said Himmelberger, who also published a 2007 anthology, Leo Holub: A Lifetime of Photography. "In the last few years, more than anything that frustrated him was that he was starting to lose his eyesight and he couldn't work in the darkroom anymore.

"He had over 80,000 negatives and Leo is the only person who has seen them on a contact sheet," said Himmelberger. "I suspect there are some gems in there that the public has never seen."

Leo Holub is survived by his wife Florence; two sons, Jan of Grass Valley and Eric of San Francisco; and a brother, Richard, of Grass Valley. Stanford is accepting contributions to the "Leo Holub Fund for Photography," a fund that will provide support for the photography program of the school's art history department: c/o Elis Imboden, Department of Art and Art History, Stanford, CA 94305.

When the Light Was Right – A Selection of Leo Holub's Work

Little girl and pigeons, 1963

Drawing class at Stanford University, 1963

Coit Tower from 45 Castle Street, S.F., 1946

Ferry Building, 1950

Imogen Cunningham on my back porch, 1972