RETURN TO HOME PAGE

FEEDBACK

|

October

2009

RETURN TO HOME PAGE FEEDBACK |

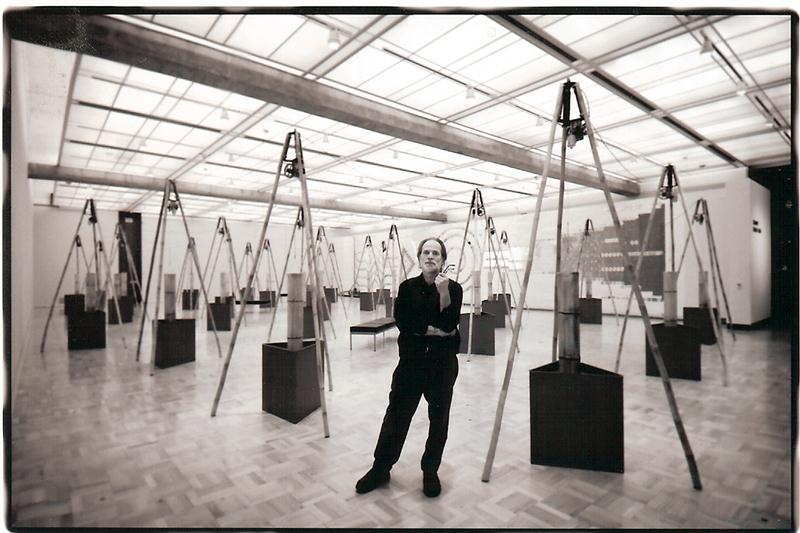

Trimpin, the eccentric subject of a documentary by Noe Valley

filmmaker Peter Esmonde, poses in front of his art installation "Sheng

High," which uses reeds encased in bamboo to deliver sound through the

space.

Photo by Matthew G. Monroe

By Lorraine Sanders

Sometimes a filmmaker's biggest challenge takes place before the cameras even start rolling. Such was the case for local documentary producer and filmmaker Peter Esmonde, who set out in 2005 to find the most genre-defying, mind-blowing, genius-wielding creative subject he could, for what would eventually become his first feature-length film, Trimpin: The Sound of Invention, screening this month at the Mill Valley Film Festival and the San Francisco DocFest."In a culture that values money, efficiency, productivity, and celebrity, I wanted to find an artist for whom the craft is the most important. I needed to find that person at that point in my life," says Esmonde, who studied film at Yale University and the American Film Institute Conservatory and has spent a decade working in the film industry and for such companies as PBS and the Discovery Channel.

As it turned out, finding the right subject wasn't the hard part for Esmonde, who lives on Eureka Street with wife Anne and son Ian, 13. "The name Trimpin kept popping up," Esmonde recalls, remembering a conversation with San Francisco artist Camille Utterback, who, like Trimpin, is a MacArthur Fellow--the recipient of a "genius grant" from the MacArthur Foundation.

Trimpin, 58, is a Seattle-based sound artist and inventor who only uses his last name. He's best known for creating highly complex installation projects, such as a 60-foot tower of self-tuning electric guitars made for Seattle's Experience Music Project, and a giant Seismofon, installed in the Minnesota Science Museum, which uses software algorithms to convert real-time seismic data from earthquakes into music.

Finding Trimpin was relatively easy, says Esmonde. Convincing him to take part in a film about his life and work wasn't.

"It was basically like the naturalist stalking the wildebeest," quips Esmonde.

Trimpin is notoriously publicity-shy and wary of the commercial art world. Despite his critical success--he's also a Guggenheim Fellow--Trimpin has never been represented by a gallery or recorded his music for commercial purposes, nor does he have a dealer, manager, website, or even a cell phone.

But Esmonde persisted, traveling to visit the artist in his funhouse of a studio, piled high with all manner of reclaimed objects waiting to become the moving parts of Trimpin's next project.

"Getting Trimpin's trust, that took some doing. That was a hurdle," Esmonde says.

Eventually, and with much coaxing, the artist agreed to take part in the film. Esmonde's next challenge? Actually filming Trimpin, who moves constantly and without warning from object to object, much like a bearded butterfly in a flower garden. Esmonde chose to use a handheld camera and a direct cinema approach for the film. Nothing was scripted, staged, or reshot.

"He's very much somebody who is looking at things on the fly. That handheld approach gives that sense of immediacy. And to try to set up a tripod in that guy's studio and try to have him stay within the frame would have been impossible," Esmonde says.

Filmed over a two-year period, the documentary follows Trimpin as he collaborates with the members of the San Franciscobased Kronos Quartet. During the shoot, Trimpin journeys to his childhood home in Germany's Black Forest region and constructs various projects, including a perpetual motion sculpture and a gallery-sized bamboo pipe organ "played" by infrared sensors.

As Esmonde films, Trimpin fashions everything from slide projectors to wooden clogs into instruments playing scores controlled by wizard-like feats of software design. He also leads the Kronos Quartet (David Harrington, John Sherba, Hank Dutt, and Jeffrey Zeigler) on a road that ends in a world premiere concert, featuring plastic toys and motion-activated instruments worn on performers' bodies.

Accompanying Esmonde's own footage are archival photographs, sound recordings of Trimpin's work, interviews with family and colleagues, and video shot by Trimpin's teenage nephew.

The result is a 79-minute portrait of an eccentric, prolific artist, capable of creating large-scale sonic curiosities as technically triumphant as they are conceptually imaginative.

So far this year, Trimpin has played at the South by Southwest (SXSW) film festival, Silverdocs, and the Seattle International Film Festival, among others.

Of course, for Trimpin the man, outcome is largely beside the point.

"He's not interested in a final product. He's more interested in the process...and to me that's fascinating," Esmonde says.

What's next for Esmonde? Along with watching his film head to festivals throughout the United States, Canada, and Europe this fall, Esmonde is currently at work on a short film about Berkeley musician Ellen Fullman, creator of a giant acoustic instrument called the long string that is played by a walking performer.

Trimpin: The Sound of Invention screens at the Mill Valley Film Festival on Oct. 14 and Oct. 16 (Trimpin and Esmonde will be present for a Q&A session). During the San Francisco DocFest, the film screens at the Roxie, 3117 16th Street, on Oct. 24 at 7 p.m. and Oct. 29 at 9:15 p.m.; Esmonde will be present for a Q&A at the Oct. 29 showing. For tickets, visit www.sfindie.com. Visit mvff.com for more information. Additional information about the film and future screenings can be found online at www.trimpinmovie.com.